Structure of a Kernel

A kernel will not be a single .c file (or at least it would be inefficient to do such). Instead, a codebase will usually consist of tons of different code and header files that are necessary for compiling and linking to a final executable.

Something like gcc is a compiler frontend, not the actual compiler engine itself. Calling gcc with some files is an intricate process that runs multiple different parts of the compilation process.

Compilation Process

Recall how object modules and linking work.

First, we go through the cpp (C pre-processor) which will ensure that the defines, imports, and preprocessor directives that are in files are injected with their actual values or whatever is necessary. This computation is happening at preprocess time, so it has no runtime impact.

Then, the preprocessed code is able to go through the compiler itself, which is cc1 for C programs. At this point, the compiler performs a variety of scalar optimizations, like constant folding.

That compiled code, which is now in assembly, is then passed to the assembler for the platform.

The assembler generates machine code which is then consumed by the linkage editor (linker) which then finally takes in all of the files to produce a runnable binary.

The .a file extension signifies a collection of .o object files.

Shared Object Files/Dynamically Linked Libraries

Note: there is also the possibility of shared object files (

.soLinux,.dllWindows,.dylibmacOS). These can be referenced by other programs without necessarily needing to copy the actual object file to the program. It helps with decreasing program size.In the above picture, you can see the inclusion of

libc.soas a reference in the linking stage.

Additionally, you also need to have a LinkerScript (.ld) file that defines the way the compiler will place object sections in memory. This is very important for embedded systems and kernels that are running directly on hardware. It defines where things exist in memory, where data will be, how things should be loaded into memory, etc.

Why have I never needed to write a LinkerScript?

The compiler provides a default when there is no linker script explicitly defined. This allows for defining a stable linked executable for a machine, without giving the user control over placement in memory.

In a kernel, you need to have direct control over where things will be placed by the compiler to ensure hardware works correctly. We can usually ensure things happen with __attribute__(<attribute>) (compiler extension directives) in order to tell the compiler to do something. In C++, we can do [[<attribute>]].

Structure of a Compiled Object

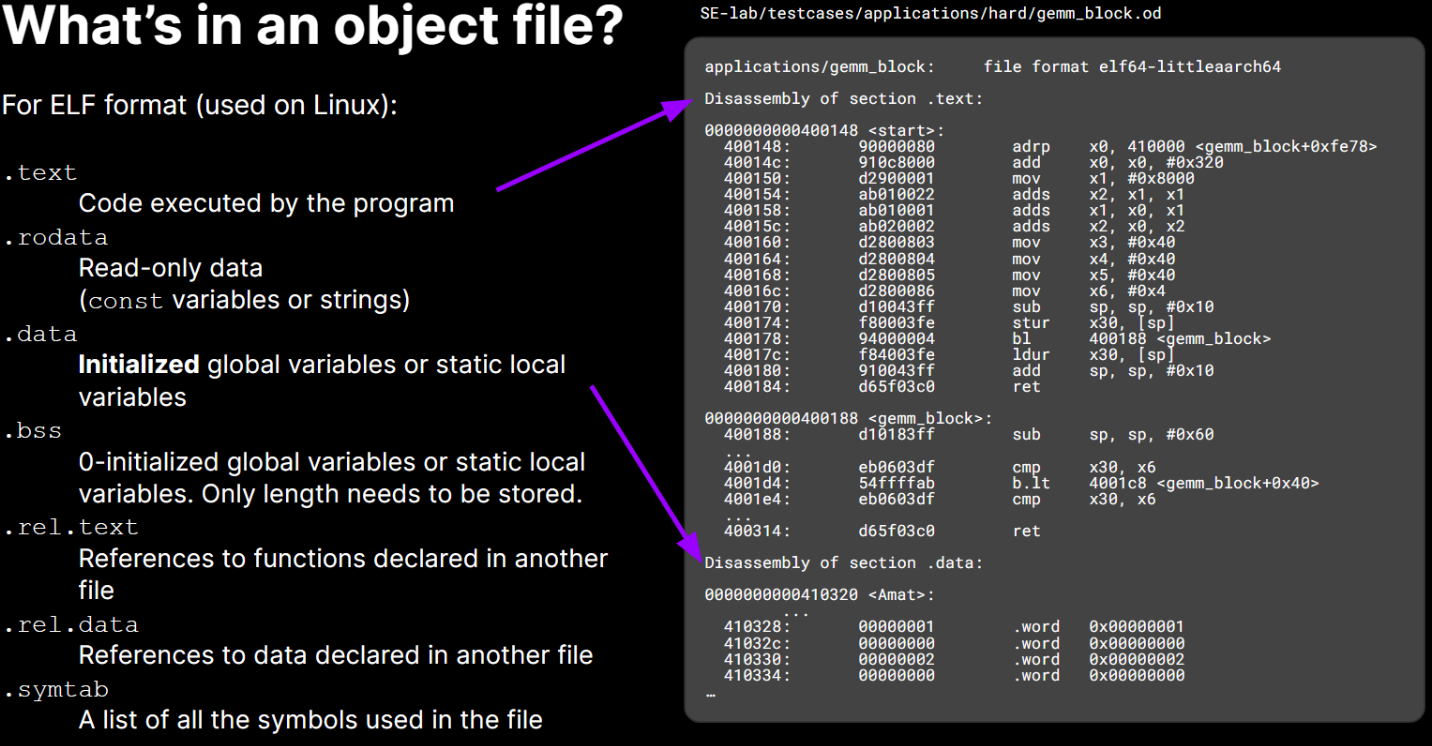

The common Linux ELF format contains the following:

ELF Format Structure

Link to original

ELF header (16 Bytes) bootstrapping information for the file .textMachine code of compiled module. All the code goes into this section. .rodataRead-only global data ( printfformat strings, jump tables, etc.).dataInitialized global/static C variables .bssUninitialized static C variables, including those initialized to 0 (saves space) .symtabSymbol table — contains all the labels (functions) so that they can be “linked” between files .rel.textList of .textlocations that need to be ‘relocated’ (modified).rel.dataList of .datalocations that need to be ‘relocated’ (modified).debugopt Debugging symbol table — allows the debugger to map binary to source .lineopt Mapping between C line #‘s and instructions in .text.strtabString table for symbols in .symtab,.debug, and section names.

This serializes all of the strings (takes all of the strings in the file and puts them into a flattened array, with each string’s null terminator encoded). This allows us to string turn pointers into indices to an array for the runtime.Section Header Table (SHT) Fixed-size entries describing each section. The ELF header describes where to find this header, and how many sections it contains