Code Generation Strategies

Simple method: generate stack code

- All variables and user-defined temporaries are allocated on stack

- use registers as temporaries when evaluating expressions

- x86: and to return values from function calls

The better strategy is to use registers because they are faster and part of the execution cycle itself.

- Local variables and user-defined temporaries can be allocated to registers if you have enough

This also means we can use registers to return values from function calls to perform some instructions.

The approach is to generate “abstract” assembly code in which you assume you have an unbounded number of registers and perform register allocation.

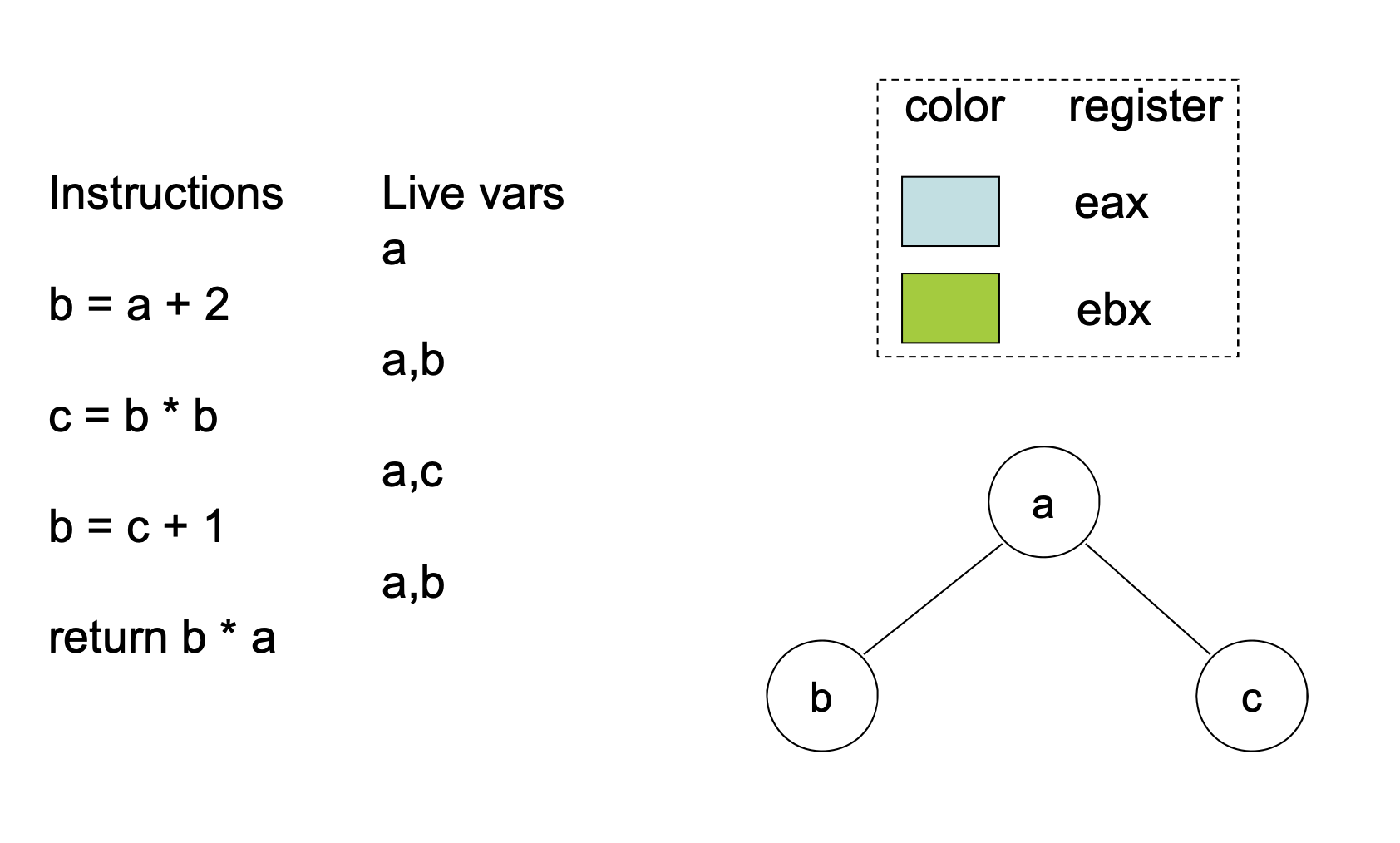

We want to assign temporary variables to some fixed set of registers. To do this, we first need to know which variables are live after each instruction.

- two simultaneously live variables cannot be put into the same register

- This makes sense because you might have to access them both in one cycle.

In addition, we also want to make sure that we save and restore register state, so we want to limit register usage.

Method

For every node in a CFG, we have

- this is the set of temporaries that are live out of

Two variables interfere if:

- both are initially live

- both appear in for any

How to allocate register to variables?

We use interference graphs and graph coloring theory.

Interference Graphs

This follows graph coloring theory.

The nodes of the graph are variables and the edges are variables that interfere with one another. Nodes will be assigned a color corresponding to the register assigned to the variable. Two colors can’t be next to another in the graph.

Graph Coloring

There are a few questions that come up regarding graph coloring:

- Can we efficiently find a coloring of the graph whenever possible?

- Can we efficiently find an optimal coloring of the graph?

- How do we choose registers to avoid move instructions?

- What do we do when there aren’t enough colors (registers) to color the graph?

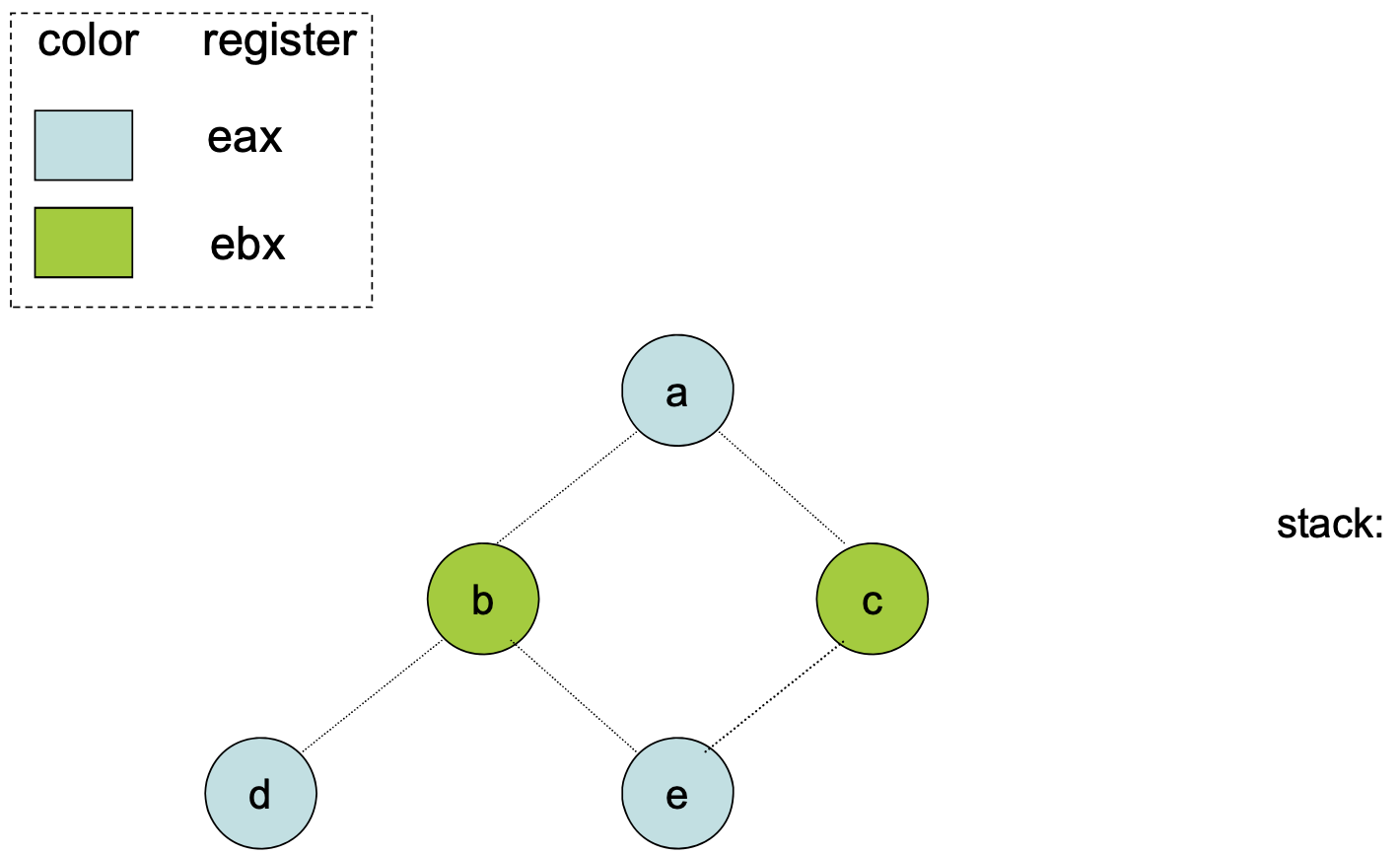

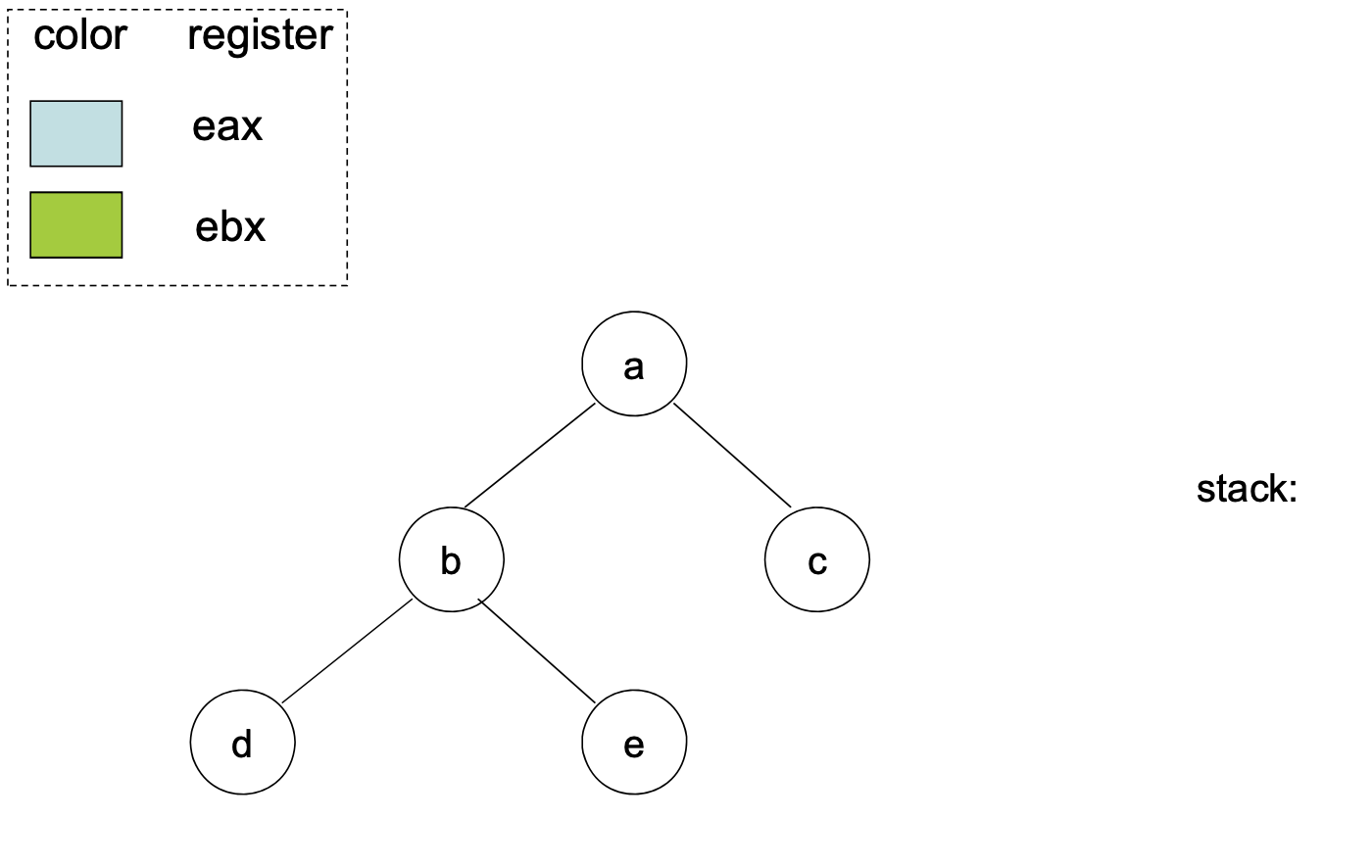

Kempe’s Heuristic

Kempe’s algorithm for finding a -coloring of a graph.

Step 1 (Simplify):

Find a node with at most edges and cut it out of the graph. We remember this node on a stack for later stages

The intuition behind this step is that once a coloring is found for the simpler graph, we can always color the node we saved on the stack.

Step 2 (Color):

When the simplified graph has been colored, add back the node on the top of the stack and assign it a color not taken by one of the adjacent nodes.

Recursive

This algorithm/heuristic can be applied recursively, allowing you to color every node by coloring recursive subgraphs.

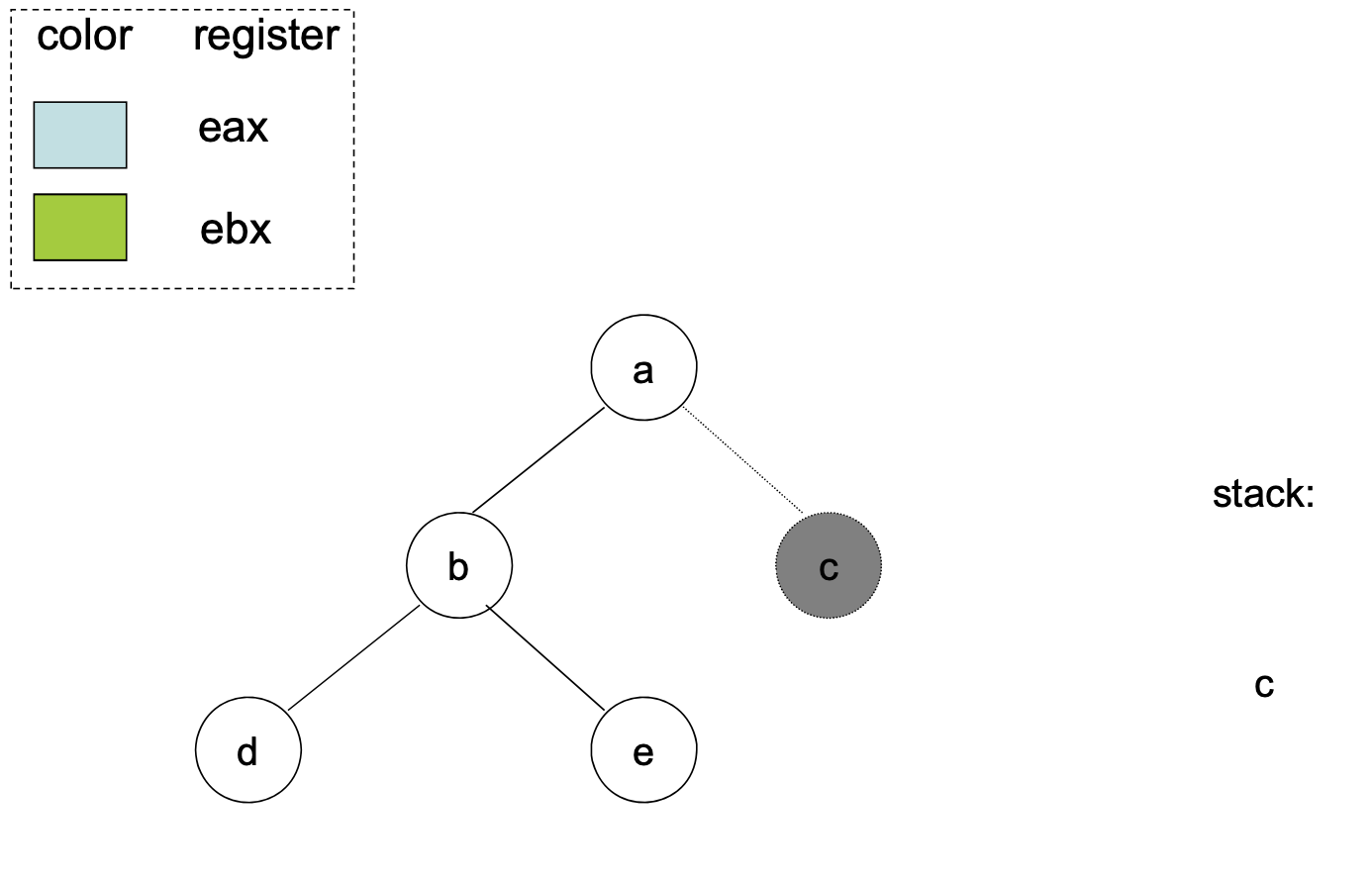

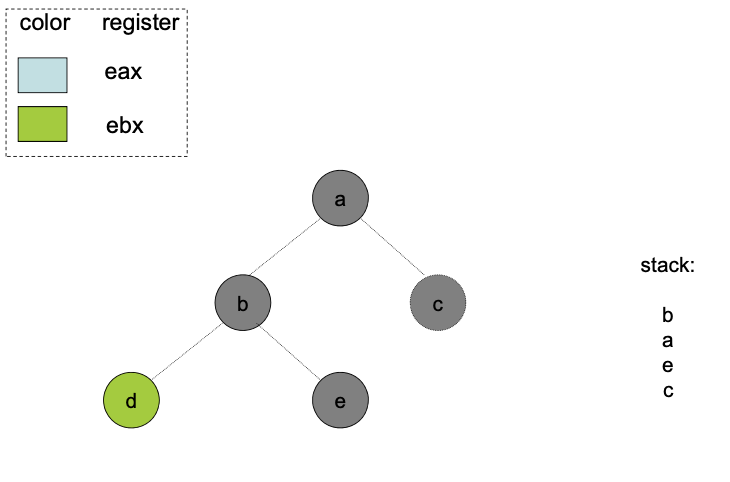

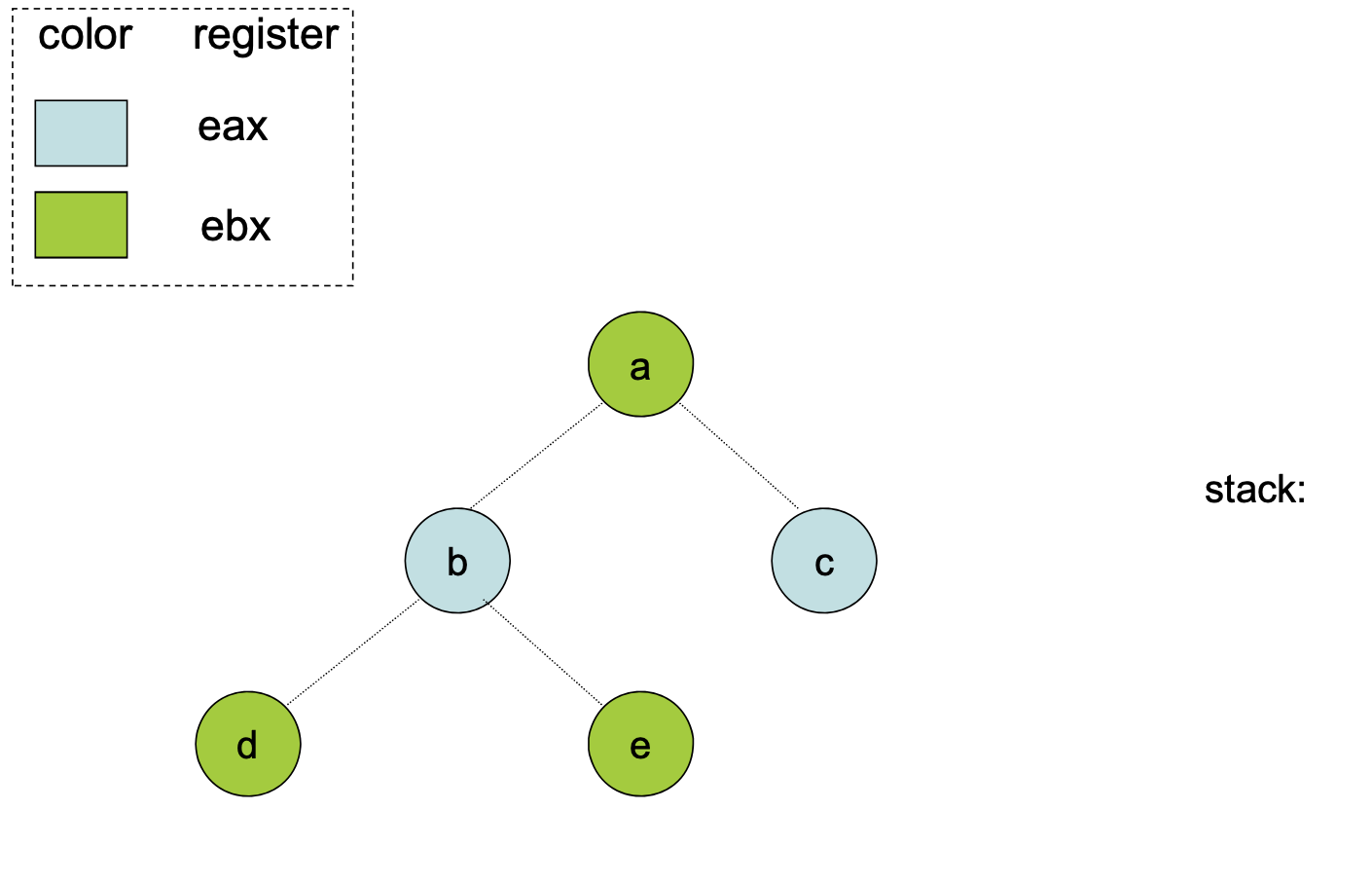

Example

Given this graph:

| Graph | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Add node with K-1 or less to the stack |

| |

| Recursively continue the process | |

| Pop off the stack and assign node a free color |

| |

| https://www.cs.utexas.edu/~pingali/CS380C/2025/lectures/Register%20Allocation.pdf |

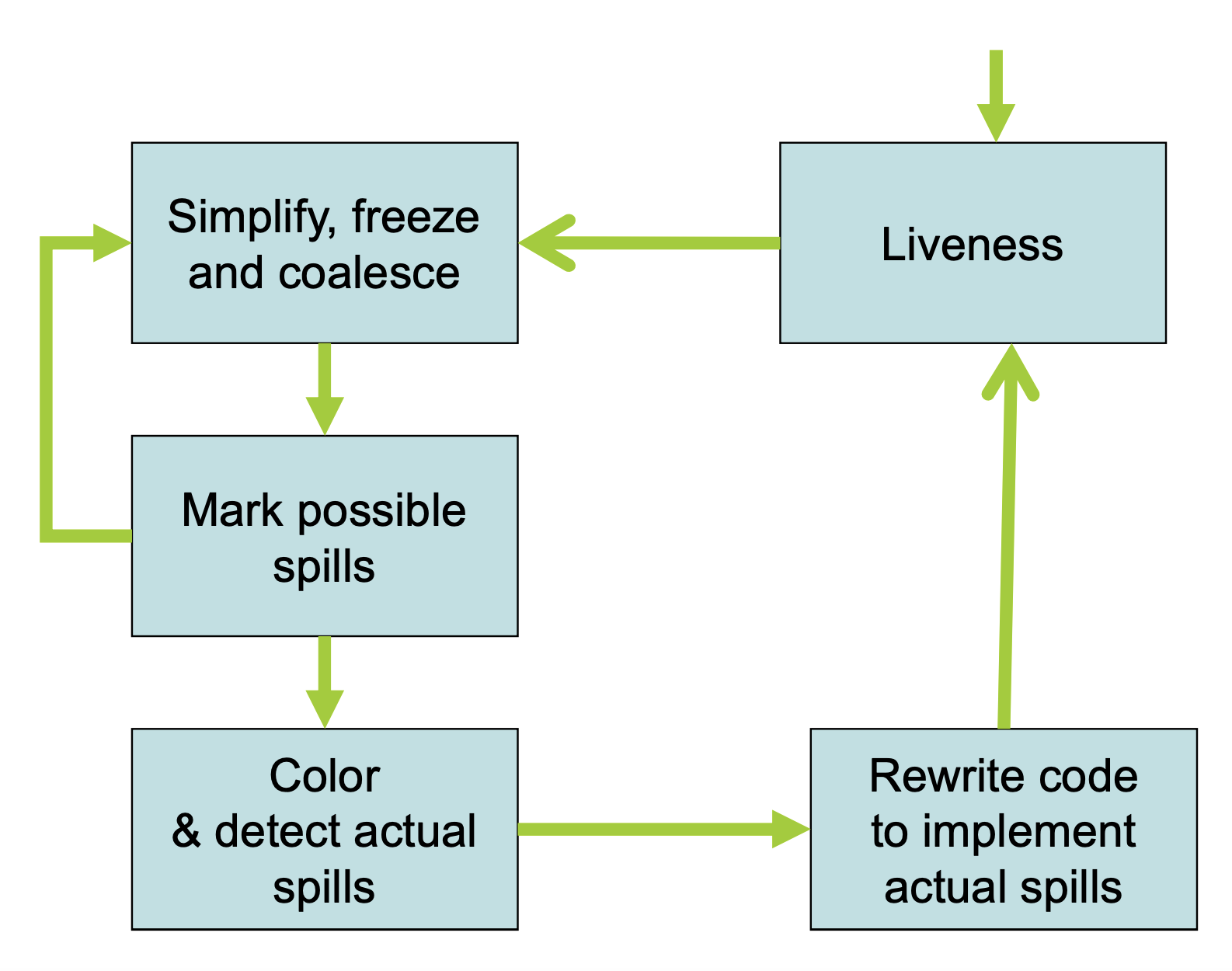

Failure

if the graph cannot be colored, it will eventually be simplified to a graph in which every node has at least neighbors. Sometimes, the graph is still -colorable, finding a K-coloring in all situations is NP complete, so we have to approximate.

Step 3 (Spilling):

Sometimes, a graph can’t be colored with colors. Then, at that point, we have to choose a variable to put onto the stack. We want this to be out of the critical path, so if possible, we try to remove a variable that is used outside of an inner-loop.

Not selecting variables in an inner-loop is just a general heuristic, and there are many others that can be used in addition (or replacement) of this one.

Spilling Code

Suppose we had to spill some variables to the runtime stack, when we want to operate on them, if it is a RISC ISA, we have to load them into a register before using them. If we used up all our registers, though, we have an issue.

The stupid approach would be to always keep extra registers handy for shuffling data in and out.

The better approach is to rewrite code introducing a new temporary and rerun liveness analysis and register allocation. The intuition behind this approach is that you were not able to assign a single register to the variable that was spilled but there may be a free register available at each spot where you need to use the value of that variable.

x = <some expression>

x = ...

...x uses...

// code range where x is not live

x = <some expression>

...x uses...can be rewritten to be:

t1 = load...

t1 = ...

...t1 uses...

// code range where t1 is not used

t2 = load...

...t2 uses...

Pre-colored Nodes

Some variables are pre-assigned to registers (e.g., mul on x86/pentium uses eax and defines eax, edx; call on x86 defined caller-save registers eax, ecx, edx)

Treat these registers as special temporaries before beginning, add them to the graph with their colors.

A caveat that arises is that you can’t simplify a graph by removing a pre-colored node. Pre-colored nodes must be the start of the coloring process. Once simplified down to the colored nodes, start adding back in the same way explained earlier.

Optimizing Moves

Code generation produces a lot of extra move instructions

- mov t1, t2

- t1 and t2 are said to be move-related

- If we can assign t1 and t2 to the same register, we do not have to execute the mov

- If t1 and t2 are not connected in the interference graph, we coalesce them into a single variable

Coalescing

The problem with coalescing is that it can increase the number of interference edges and make a graph uncolorable, so there are two solutions:

- Briggs: avoid creation of a high-degree () nodes

- George: can be coalesced with if every neighbor of :

- already interferes with , or

- has low degree ()