Part of the Multiprocessor Issues lessons.

Consistency Models

Consistency models, model, the behavior of multiprocessor systems. They describe how instructions can be reordered across the local and global memory orders.

In comparing consistency models, we compare executions and implementations.

A consistency model is strictly more relaxed (weaker) than a model if all executions are executions, but not vice-versa. Two models may be incomparable.

What makes a good consistency model (the 4 Ps)

Programmability: Should make it relatively easy to write multithreaded programs

Performance: Should facilitate high-performance implementations at a reasonable power, cost, etc.

Portability: Should be adopted widely.

Precision: Should be precisely defined, usually with mathematics.

Shared Memory Parallelism

There are multiple processor cores, each of which may read and write to a single shared address space.

What does correctness of such a shared memory system mean?

Memory consistency

Cache Coherence

Consistency vs. Coherence

Consistency is a precise, architecturally visible definition of shared memory correctness. This provides rules about loads and stores and how they act upon memory. It also usually allows many correct executions while disallowing many more incorrect ones

Coherence is a microarchitectural means to supporting a consistency model. In a shared-memory system with caches, the cached values can potentially become out-of-date (or incoherent) when one of the processors updates its cached copy of a shared value. Coherence seeks to make the caches of a shared-memory system as functionally invisible as the caches in a single-core system by propagating one processor’s write to other processor’s caches.

Coherence issues arise because of one fundamental issue: there exist multiple actors with access to caches and memory. In modern systems, these actors are processor cores, DMA engines, and external devices that can read and/or write to caches and memory.

Example of Incoherence

| Time | Core C1 | Core C2 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | S1: A = 43 | L1: while (A == 42) |

| 2 | L2: while (A == 42) | |

| 3 | L3: while (A == 42) | |

| 4 | … | |

| 5 | Ln: while (A == 42) |

If the change in Core C1 is not eventually made visible, Core C2 will keep running forever. That is not a designed, nor desirable outcome.

If a chance by Core C1 to A’s value in its cache is not made visible to

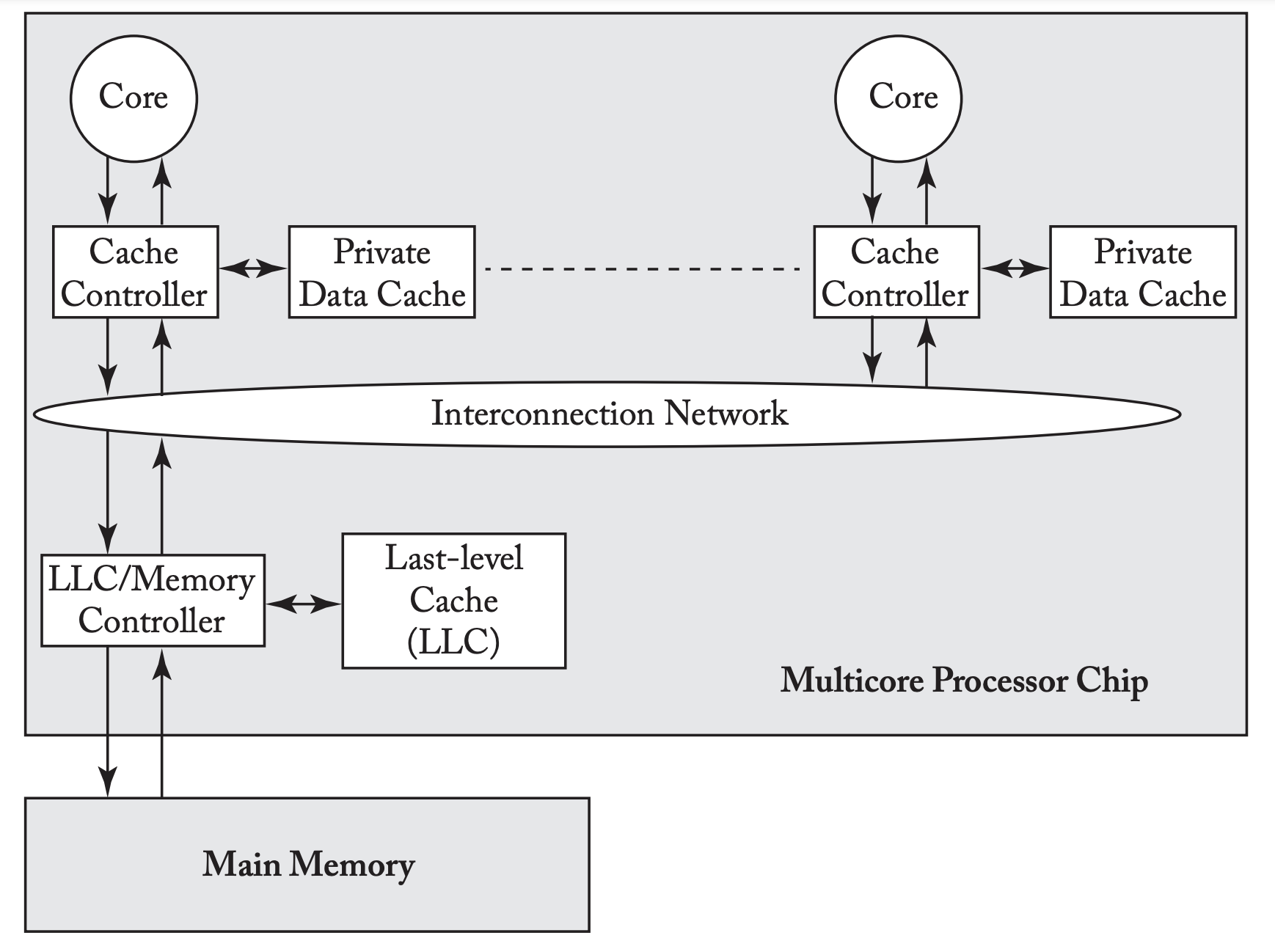

Baseline System Model

All cores can perform loads and stores to all physical addresses.

Each core is single threaded.

Each core has a private, write back, physical index, physical tag (PIPT) D$ (cache Cache Organization).

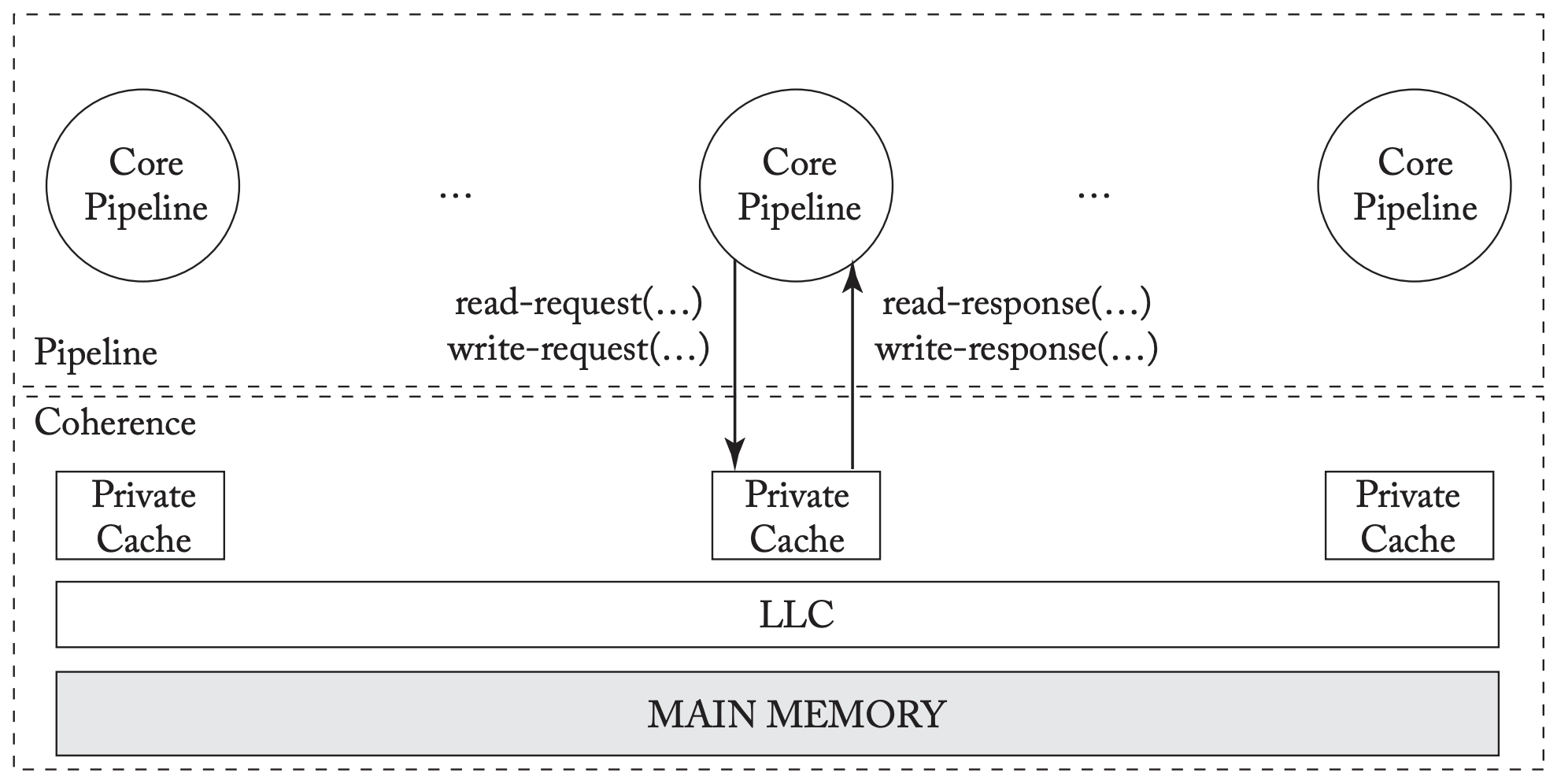

Pipeline-Coherence Interface

Informally, a coherence protocol must ensure that writes are made visible to all processors. The processor cores interact with the coherence protocol through a coherence interface with two methods:

- A read-request method

- A write-request method

A coherence protocol can be either consistency-agnostic or consistency-directed.

In a consistency-agnostic protocol, a write is made visible to all other cores before returning (i.e., writes are propagated synchronously). The interface becomes that of an atomic memory system with no caches present.

In a consistency-directed protocol, a write can return before it has been made visible to all cores (i.e., writes are propagated asynchronously). These emerged to support throughput-based GP-GPUs and heterogeneous systems.

Consistency-Agnostic Coherence Invariants

We need two variants to describe this approach:

- Single-Writer, Multiple Read (SWMR) Invariant

- Data-Value Invariant

Coherence Invariants

Link to original

SWMR Data-Value For any memory location A, at any given time, there exists only a single core that may write and read to A or some number of cores that may only read A. The value of the memory location at the start of an epoch is the same as the value of the memory location at the end of its last read-write epoch.

Consistency

Sequential Consistency (SC)

A single core is sequential if the “result of an execution is the same as if the operations had been executed in the order specified by the program.”

A multiprocessor is sequentially consistence if “the result of any execution is the same as if the operations of all cores were executed in some sequential order, and the operations of each individual core appear in this sequence in the order specified by its program.”

The total order of operations is called memory order. In sequential consistency, memory order respects each core’s program order .

SC Formalism

Notation:

- : load to address (block address)

- : store to address (implied value input)

- : atomic read-modify-write to address

- : local program order are core

- : global memory order

An SC execution requires the following:

All cores insert their loads and stores into the order respecting their program order, regardless of whether they are at the same or different addresses ( or )

Every load gets its value from the last store before it (in order) to the same address:

An SC implementation permits only SC executions (safety) and eventually makes a store visible to a load that is repeatedly trying to load that location liveness.

Basic Implementation Using Black Box Cache Coherence

For now, we’ll treat the cache coherence as a block box of the SWMR invariant.

The intuition behind the implementation is that L1 caches can be in 2 states: 1) modified (M) for a block that a single core can write and read or 2) shared (S) for a block that one or more cores can only read. L1 caches use GetM and GetS coherence requests to obtain a block in M and S, respectively.

Total Store Order (TSO) Consistency Model

This was introduced by Sun Microsystems (the creators of Java) in their SPARC systems. x86 appears to match this memory consistency model (no formal proof of this). RISC-V supports a TSO extension called RVTSO.

The motivation for this was for longstanding support for write buffers (for performance reasons). For a single processor, a write buffer (WB) along with load bypassing makes the write buffer architecturally invisible.

Does this continue to work for multiple cores, each with its own bypassing write buffer?

No, read below.

Assume a multicore processor with in-order cores, each with a single-entry write buffer.

| Core C1 | Core C2 |

|---|---|

| S1: x = NEW | S2: y = NEW |

| L1: r1 = y | L2: r2 = x |

The following execution can happen:

- C1 executes S1 and buffers the value NEW in its WB

- C2 executes S2 and buffers the value NEW in its WB

- Both cores perform their loads (L1 and L2), obtaining the old values of 0

- Both cores’ WBs update memory with the new values

This is a non-SC execution. Without the WBs, the hardware is SC, with them, it is not.

WBs are architecturally visible in a multicore processor.

TSO is a consistency model that allows this outcome and permits the use of a simple FIFO write buffer at each core.

TSO Formalism

Notation:

- : load to address (block address)

- : store to address (implied value input)

- : atomic read-modify-write to address

- : local program order are core

- : global memory order

- FENCE: synchronization instruction; when executed by core , ensures that ‘s memory operations before the FENCE according to the local program order get placed in before ‘s memory operations after the FENCE.

A TSO execution requires the following:

Every load gets its value from the last store before it (in order) to the same address:

s order everything: